Eureka Blog

How is coffee roasted?

Our journey around the coffee drupe began on its long and fascinating journey rich with traditions and culture, stories and landscapes that takes the very coffee bean from its plantation to our cup, written with an answer to our questions.

How is coffee roasted? It is another question that starts this third itinerary and to answer it, we will go into details about the skills and competences that are necessary in this fundamental landscape: the journey in which our coffee bean becomes great!

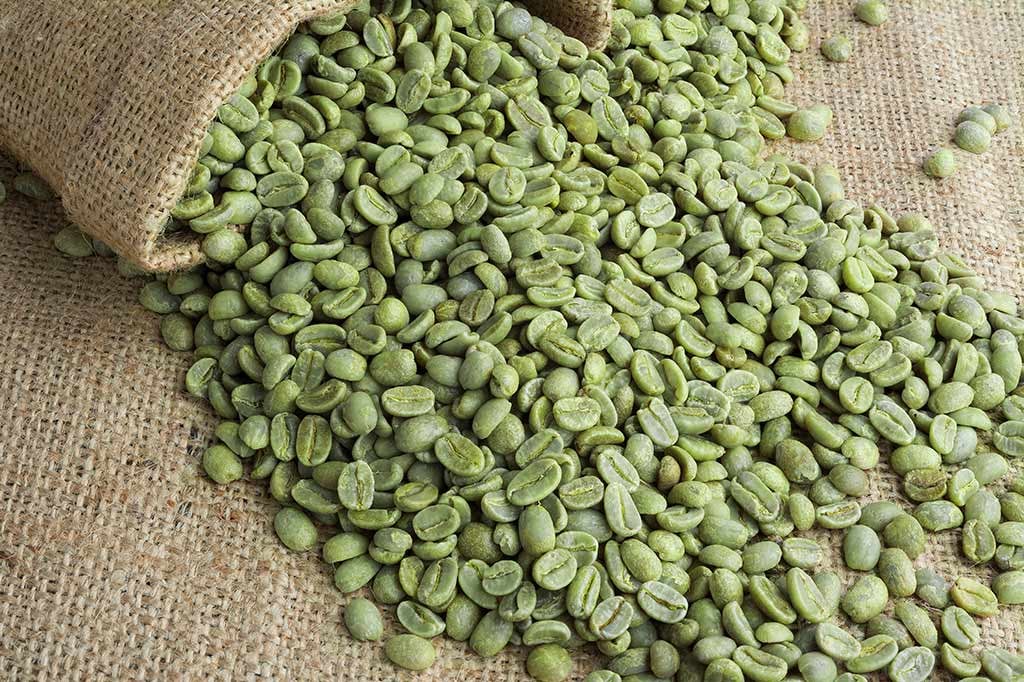

From the plantation to the importing countries

Green coffee, also known as raw, is exported by producing countries and imported by practically the entire world, given that no producing country exists that produces enough for its consumption and thus it has to import it from others.

European countries import about half of the world production, while the United States on their own import about one quarter of the entire production, thus ranking as one of the major coffee importers. The gold medal for the highest consumption per capita goes to Finland, now a few years it has been first in this ranking with an impressive 9.6 kg consumption of coffee per person (equal to 2.64 cups/a day), followed by the nearby Scandinavian nations.

Every year over 150 million bags of green coffee (60 kg bags) are sold, and over 100 millions are the people that benefit from coffee, from the producer that takes care of the plan, to the barista, that every day opens his coffee shop.

Among these numbers we find various types of individuals: local merchants, importers, broker, roasters, distributors, coffee machine makers, specialised technicians, trainers and many others that enrich and add value to the long and complex coffee supply chain.

The roaster usually acquire the green coffee from importers that must guarantee a specific amount always available during the entire year, having the possibility of storage: others instead prefer a direct relationship with the producer (an increasingly popular trend among small roasters.) In this way, a strong relationship between producer and roaster is built, with the roaster often going in person to assess the plantation, negotiate the price and discuss the quality of the harvesting.

Unfortunately, the cost of coffee follows the rules and principles that determine the price of any good that goes to market, with the fluctuation between demand and supply prevailing over the quality of the product. Poor harvest, caused by natural events (weather or disease related), the instability that at times characterises the governments and economies of the majority of the producing countries, all affect the coffee market that is on its own already quite uncertain.

How coffee is roasted: the role of the roaster

Green coffee, even if of high quality, is in general a product characterised by a weak aroma and is not pleasant to the palate. The qualities that make coffee pleasant to the taste and with a good aroma, in fact, are gained from the changes the coffee bean goes through during the roasting process.

To explain best how coffee roasting occurs, we have to define the meaning of this processing phase: roasting is nothing more than the dry cooking of the green coffee bean, so as to transform through chemical reactions the organic substances present (more than 800 ingredients responsible for the aroma) and induce the physical changes that make their extraction possible. This is a centuries-old process, of course, but that in the past few years it has become highly studied and sophisticated.

Technologies and scientific research help the roaster, a professional figure able to determine the quality of the roasted coffee, thanks to the experience and competence level with which he carries out his work.

The activity of the roaster is summarised in the revelation, through the roasting, of the aromatic potential between the different varieties and origins of the beans of which the coffee is a biologically carrier, guaranteeing the ability to repeat the same 'cooking' for each roast, thanks to the competence and skill in the craft.

Before everything else, the roaster must have good knowledge of all the types of coffee beans. It possible to compare a roaster to a chef, since timing and temperature are fundamental just as much as in the kitchen as in roasting, where different beans have different requirements. Although all coffee beans may look the same, in addition to the different processing method after harvest, they also reveal different sizes, densities and humidity, details that often require exclusive attention.

Another skill by the roaster is the tasting, a necessary skill to recognize the quality of the raw material and the quality of the work carried out. Cupping, or the tasting of coffee, is ever-present after a roasting, as it is the best way to define the percentages of the coffees to be mixed. Thus, it is possible to define a blend as the artistic expression of the coffee roaster, exclusively developed according to his/her subjective taste.

Which are the main levels of coffee roasting?

Typically they are light, medium and dark: the three hues through according to which roasted coffee is classified even if there are alternative names that specify more accurately various possible colour shades. These subdivisions are possible thanks to the use of a colourimeter, a device that allows ‘measuring’ colour, that is to specify the percentage in it of the three primary colours (yellow, red and blue) that generate the entire range of possible hues. The colorimeter compares the light intensity of the sample over a preset scale.

Light roasted beans are more opaque and slightly rougher respect to the dark roasted ones which, instead, have a rounder, swollen and glossy surface. The reason is due to the structure of the bean, which in the light roasting version, presents a cellular structure that is not particularly expanded within which the aromatic oils, formed during roasting, remain trapped; the dark roasted beans, instead, have a more open and ‘spongy’ structure that promotes a faster migration of the oils to the surface.

‘The lighter the roasting and more acidic the flavour in the cup’ is a general rule that well goes with a ‘darker roasting, the less acidic the flavour in the cup’

its natural alter ego. Between these two extremes there is an entire world of balancing and percentages that turns up in our cups, in an infinite alternation of sweet and bitter flavours.

Finally, it should be said that light roast maintains the flavours and notes that are truer to the coffee bean, while the darker and more roasted the bean, the more the aromas derive from chemical processes (such as the caramelisation of sugars) and the endothermic reactions of roasting.

Choosing the right coffee roasting technique

The roasting machine is the heart of the roasting process. The machines are of various sizes, with a wide range of capacity from a few kilograms to several hundreds, highly computerised or fully manual. Let's review this topic in more details!

Let's start with a introductory classification of the three main roasting techniques:

- the direct flame technique is the most ancient method, and it consists in engulfing the container containing the coffee with a direct flame: in this manner heat is transferred by conduction, both between the metal surface and the beans and among the individual beans;

- the air technique, where air heated by a burner is channelled inside a roasting drum that contains the coffee. This is the most popular method at this time;

- finally, the fluid bed technique, due to its discontinuity, is almost exclusively suitable for small quantities: here the coffee beans are roasted using hot air, almost if floating, with a slight over pressure.

Cooling is fundamental at the end of the roasting process and it must take place as fast as possible! This to avoid that, due to exothermic reactions in progress, the roasting level exceeds the desired one: in other words, it is necessary to avoid that the roasted coffee, due to the constant heat exchange always active between bean and bean, keeps roasting.

Refrigeration takes place in a large tank inside which the beans are mechanically kept moving: thanks to a large quantity of cool air freed on the roasted product, ambient temperature is reached in a few minutes from the approximately 180° C at which the beans were previously.

The just roasted coffee then needs a period of ‘degassing’. The chemical reactions following roasting, in fact, generate plenty of CO2, which at the end of the process ends up trapped inside the bean: the time it takes to get out can be as long as two weeks from the end of the roasting, a process (whose speed is inversely proportional to the time needed for the roasting) at the end of which a weight loss of approximately 1.5% respect to the initial weight takes place.